Plan Ahead and Prepare

This is the third article of a four-part series. Part 4. Part 2. Part 1.

By Neil Ginty

Contributors: Jim Westover, Brenna Daugherty, Sarah Mergy

As any camping enthusiast lured by the great outdoors knows, there is a duty to leave no trace. That is challenging with a permanent structure but the principle of design for harmony with nature and touching the ground lightly is an apt prompt towards the type of environment we, as designers, want to create.

The resiliency issues we identified in part two of this series speak to the need for sustainability in the architecture we place on the land. For part three, we identify some ecological systems that respond to a rural landscape.

The blank canvas of a pastoral site is an opportunity to optimize the benefits of your local environment through passive energy saving strategies, and even to go off-grid entirely. “Off-grid” involves a bold vision that does not rely on external utilities but instead uses water from a well or rainwater harvesting, uses a septic system or a constructed wetland for sewage treatment, and uses electricity from solar photovoltaics and wind-turbines.

The site plan from the first part of this series is the map that unlocks these passive strategies. It identifies the prevailing wind for summer cooling and where the sun will be to benefit or shield from solar heat gain.

It also provides clues as to what microclimates to expect. During the day, for example, air on mountain slopes is heated more than air at the same elevation over a nearby valley. As the day progresses, warm air rises and draws the cool air up from the valley, creating a valley breeze. At night the mountain slopes cool more quickly, which causes a mountain breeze to flow downhill.

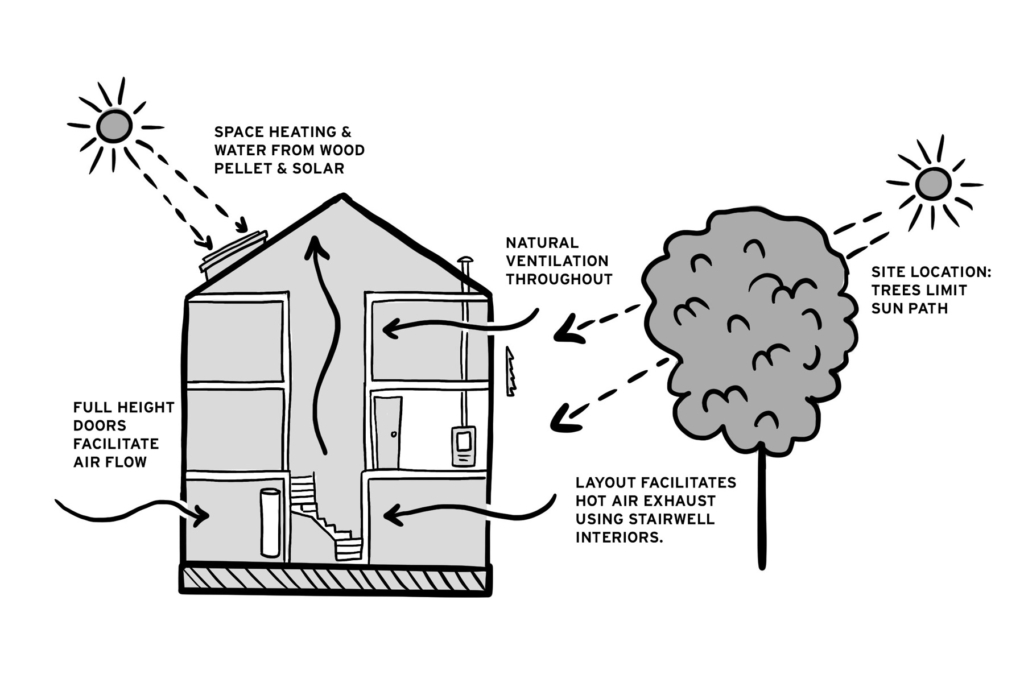

Some of those passive energy savings strategies include positioning windows to take advantage of cross ventilation and the prevailing wind, using large overhangs above those windows like at our Golden Oak project to prevent solar heat gain, and using a staircase as a ventilation chimney.

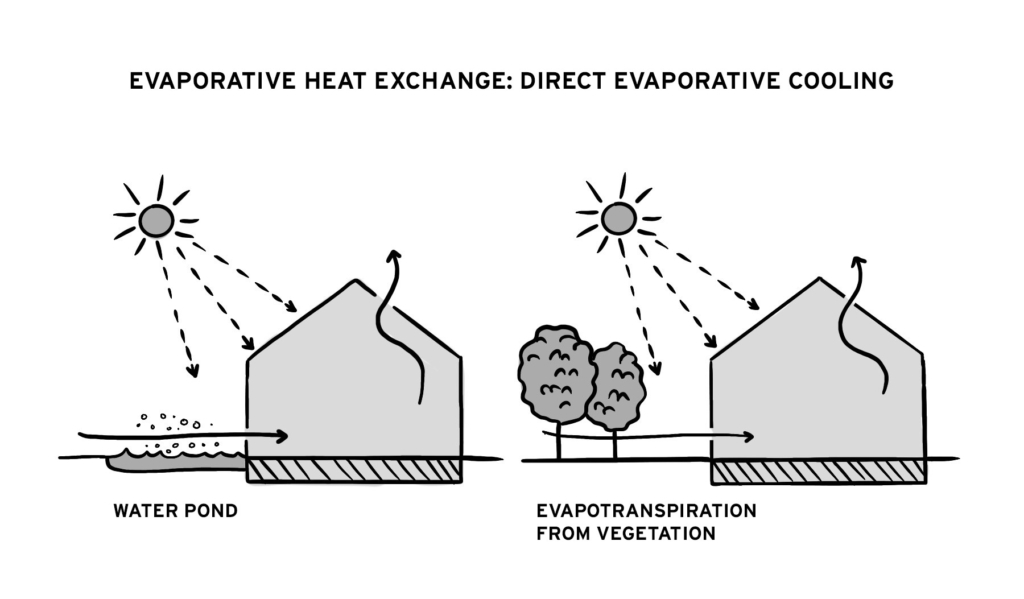

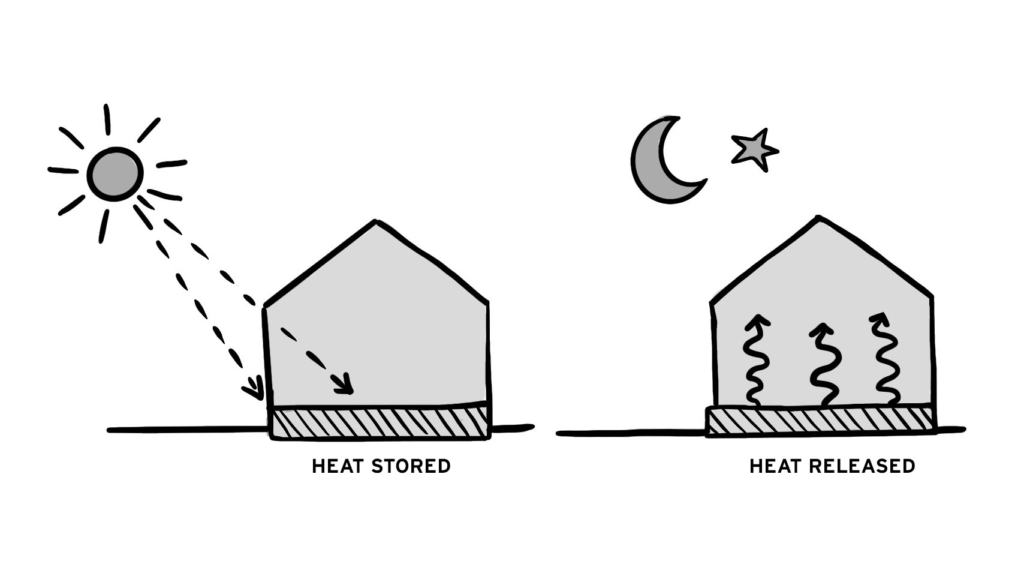

Evaporative cooling can be utilized by locating a building close to a water feature or vegetation. In climates where the nights are cold, and days are hot thermal mass walls or floors can absorb daytime heat for release through the night to maintain comfortable temperatures.

Passive strategies can only do so much for modern living, however, and more active methods of creating a sustainable environment will be necessary. In design for harmony with nature, these strategies—like rainwater harvesting, grey water reuse, and solar energy—can reduce our environmental footprint while enhancing the efficiency of the home.

The electrical power those systems require can be sourced from photovoltaic solar collectors and wind turbines. The optimal location for which would, again, be determined by the site plan drafted at the start of your project.

The HVAC system should perform to a high efficiency and be tuned to the building’s needs. Building automation can optimize this by knitting systems together through a network of electronic devices designed to monitor and control the HVAC, security, fire & safety, lighting, humidity, and audio-visual control systems within a building to create a “smart home”. It can also be applied to multiple buildings or zones within the homestead.

These strategies speak to reducing carbon emissions in the daily life of a family but one should not ignore the embodied carbon of the materials used in a home’s construction. EV charging points will be essential, but local architecture often provides design cues for more modern approaches. Vernacular designs are invariably driven by the local climate and the availability of local materials.

While recycling materials is always worthwhile, so too is recycling whole buildings such as our Big Ranch Road project which took an iconic Napa Valley barn and re-purposed it as an entertainment pavilion. As WDA Community Practice Leader David Plotkin notes, “It can be easier to build from ground-up, but a significant carbon emissions come from building materials and waste generated for new construction projects. By repurposing existing buildings, we can preserve resources and reduce our carbon footprint.”

Even a ground up construction can be designed with a view to future adaptive reuse. A smaller primary residence with an “Accessory Dwelling Unit” (ADU) attached or close by is one way to create a more adaptable home that can react to the natural evolutions of a family.

This is the third article of a four-part series. Part 4. Part 2. Part 1.

Contributors: Jim Westover, Brenna Daugherty, Sarah Mergy