One of the truisms in design is that creativity loves constraints and a challenge. What happens, then, on an open landscape when those constraints are much less obvious? Estate architecture and landscape design offer a unique opportunity to shape a site with artistic intention, balancing creativity with the natural environment to create something both timeless and contemporary.

A rural, untouched site presents the blankest of canvases on which an architect, together with their commissioning patrons as curators of the land, might make their artistic intervention. “It is an opportunity for original artistic endeavor,” said WDA Principal Jim Westover. “A chance to push the boundaries in a way that is informed by and in harmony with the landscape around it.”

The constraints, while not immediately obvious, are very much there however, along with locally sourced historical cues and clues for the architect to pick up on in crafting a design that feels contemporary in a landscape that demands timelessness. The site plan we covered in part one of this series, along with the necessary resiliency measures of part two, and the holistic approach to sustainability of part three, all help to inform the constraints that drive the architecture in estate design.

Blank Canvas

A rural landscape can feel like an overwhelming presentation of opportunities on which the architect can sculpt their intervention. “A real challenge of wide-open landscapes is that, in some senses, you don’t have constraints,” says William Duff. “That’s where it becomes very important to understand the site plan and find those constraints.”

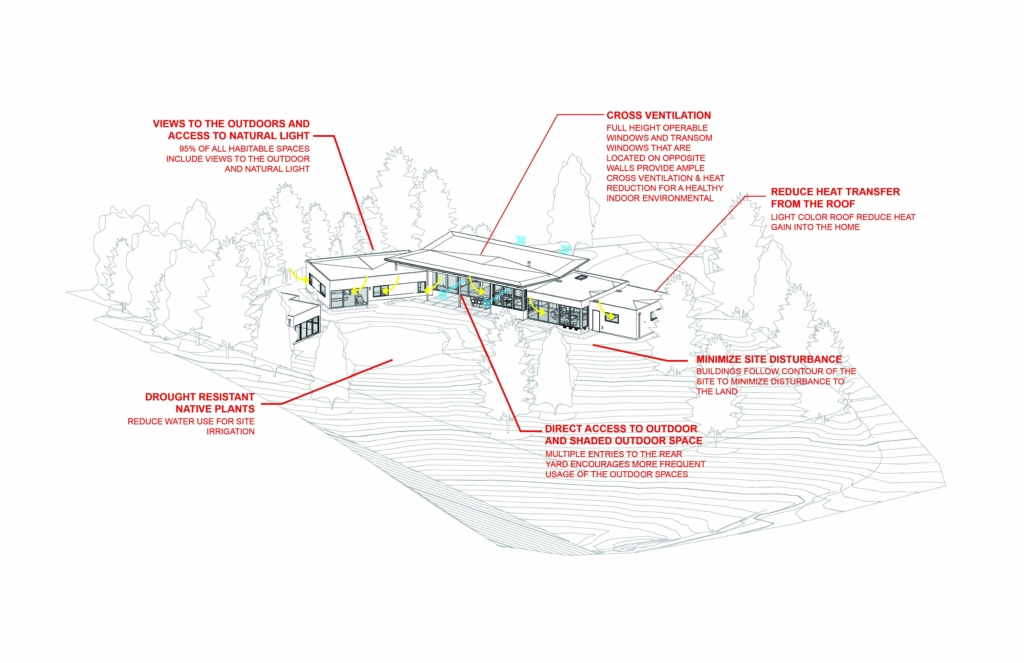

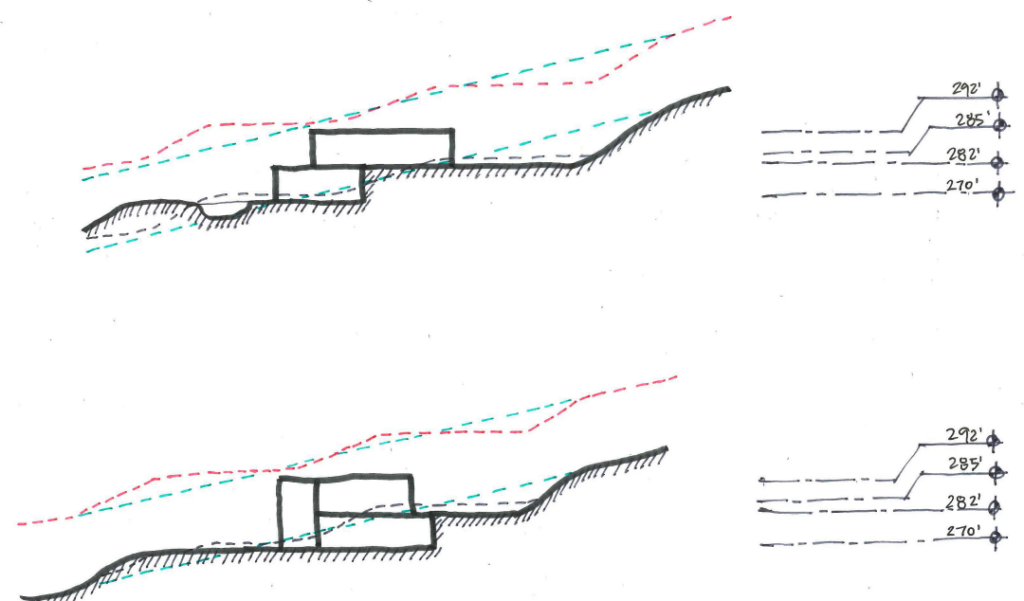

Some of those constraints will have been identified on the site plan and will include elements such as the prevailing wind, the movement of the sun, the topography of the site, and where trees or other prominent natural features are located. From this we, as architects, can start to identify the optimal locations to frame views and capture the natural benefits of a site as appropriate for how its buildings will be used.

A bucolic landscape is as timeless as a setting can get and the architect is duty-bound to respond sensitively. “Architecture and landscape should make each other better,” William said. “To make something timeless, it needs to elegantly respond to its surroundings and enhance those surroundings in a way that isn’t self-conscious or isn’t a copy but instead brings something new and makes its own statement with confidence. When you advocate for original thought and that is done well, the result is enduring.”

Forms in Nature

There are a few different strategies to establishing an architectural moment in a landscape. One starting point is for buildings to disappear into the landscape, they can be built-in, like a cave, such as the work of Emilio Ambasz which often feels like the landscape is being peeled back to reveal hints at the architecture beneath.

Another approach involves forms which create a synergy with the landscape and establish a dynamic juxtaposition to it. This method affords sculptural geometric shapes the opportunity to contrast and enhance organic and undulating vistas in which they are placed.

William Duff regularly speaks to horizontality being a key theme for the firm’s design vision. “In thinking about the horizon, that’s where the word juxtaposition comes into it,” he says. “The horizon, when you really zoom back, it’s a flat line but the land is constantly undulating. As humans we orient ourselves around the horizon.”

“Long horizontal lines reference the horizon, and it becomes an anchoring element. We mentally associate it with the horizon itself. You see a building with strong horizontality juxtaposed against the landscape and it anchors the architecture, creating a stabilizing feeling we humans get when we interact with the architecture. One of my favorite elements is seeing rolling, flowing hills enhanced by the perfect, clean geometry of a piece of architecture.”

Future Vernaculars

In rural architecture, it is worth looking for cues and clues in the vernacular design of the locality. The shared knowledge of a place, that transcends generations, will often have solutions to the same design challenges faced by contemporary architects. This is particularly true in terms of sustainability considering vernacular design was often a response to a lack of available technological solutions at the time they were devised.

“Vernacular architecture is a representation of how designers, builders, and homeowners built structures to respond to the landscape, weather and their surroundings,” William said. “Within that there are cues to help inform a current interpretation of all those same elements.”

“Our responsibility, as contemporary architects, is to create today’s interpretation of the environment. That is our artistic statement, our contribution to what tomorrow’s vernacular will be. As such, we don’t need to mimic the vernacular or what was designed before, but we do feel we should respect and learn from it and, where appropriate, use them.”

Even the necessary utilitarian structures of an estate design, such as water towers or agricultural buildings, can enhance and contribute to the landscape which host them if time, energy, and effort form part of their realization. Using resilient materials, being sensitive about site positioning by reacting to natural conditions and designing buildings that are appropriate to their function, all helps to prolong the life of a building. And, in so doing, they can continue their contribution to an enhanced landscape for much longer without continuing maintenance. The more likely they will be there for future generations and the better state it will be in when it becomes vernacular architecture in the distant future.

Connecting to Nature

In a vast landscape, the opportunity for the interior of the home to engage and connect with the outer realm at all times should be embraced. It should be articulated with restraint however by finding moments within the architecture to frame views or establish natural flows between inside and out.

“The part of the architecture that interfaces with the outside should be designed to connect with the outside world,” said William, “but when you enter more of the inner realm, refuge is not a bad thing. It should not be seen as a pejorative term. What can really make a difference in a project is restraint. Having the opportunity to frame views is the closest the architect gets to painting,” he said.

The use of natural materials is another chance to affirm the connection to the outside, even while visually disconnected from it. They provide a connection to the environment and appeal to our humanness as creatures of nature. Weather–durable materials, for the exterior, are particularly good, sustainable choices for rural architecture as they will perform into the future with little maintenance despite being regularly exposed to the elements.

A Complete Picture

The vast canvas of a landscape presents an exciting opportunity to architects to embrace the artistry of the discipline. And, as with the finest pieces of art, they ought to always have a timeless quality. Jim Westover remarks, ” When that canvas is a landscape, estate architecture and landscape interventions are an opportunity to add to the canvas and enhance it through something that feels it has always been there and, so, make it feel more complete.”

For more on estate design, please visit our full series: Part 3. Part 2. Part 1.

By Neil Ginty

Contributors: William Duff, Jim Westover, Brenna Daugherty, Sarah Mergy